Over 10 years since its introduction, systemd can still get some Linux users riled up. I happen to not be one of them. Even though I try out systemd-free distros, I’ll still likely regularly use systemd-based distros. Here are some of the reasons why.

SysVInit Had to Go

When systemd first appeared in the early 2010s, a lot of Linux users wondered why such an overhaul of the init system that Linux had used was needed.

Related

Why Linux’s systemd Is Still Divisive After All These Years

A decade after it was first introduced, systemd is still the target of some savage opposition–but why? Is the outrage justified?

The old system, System V Init, or SysVInit, had its roots in the 1980s. Back in the ’80s, Unix systems were used in a different way than modern machines. Unix was used mainly on big minicomputers and powerful workstations. SysVInit launches services sequentially, which can increase boot times. Laptops were rare in that era. USB didn’t exist, and peripherals generally were only added and removed between boots. The configuration of the system typically didn’t change throughout its runtime. Once the system was up, it usually stayed up for a long time, so boot times weren’t an issue. Hardware changes on shared systems happened rarely and were also more of a “one-and-done” experience.

Traditionally, if you added a piece of hardware, even something like an external disk drive, you would have to shut down and restart the system. SysVInit was also convoluted, with shell scripts corresponding to “runlevels.” This approach was inadequate as Linux became more widespread. With modern machines, you might plug in a USB drive or move between Wi-Fi and wired networks with a laptop. systemd can respond to such “hotplugged” hardware instantly.

It’s a testament to the strength of the idea of Unix-like operating systems that major components can be replaced as needed.

systemd Is Here to Stay

While systemd was first emerging, there was more debate and competition as to what would replace it. The debate got so heated that some Linux distro developers resigned from the stress of the constant stream of invective from Linux users.

For better or for worse, using a mainstream Linux distro means using systemd. The documentation will mention it, and if you go for support, if you run into a problem, it will likely involve using the systemctl utility.

Because systemd is so integral to the way modern Linux distributions run, most major distros are unlikely to replace it unless they have a good reason.

This wouldn’t be a far-fetched scenario. If you were using Linux in the 2000s, you might have thought that the SysVInit system would last forever. If you didn’t like it, you could use one of the BSDs.

Maybe someone will create a different init system, one that Linux developers think is better. My money would be on whatever the BSD developers cook up to replace their own aging init system. I imagine that would end up something like macOS’ launchd, which also influenced systemd.

For many Linux distro developers, systemd seems to be at least a “good enough” option. In many forms of engineering, including software engineering, you have to make trade-offs when designing things for the real world instead of trying to build the absolute best solution.

systemd Works For Me

One reason that I’ll tend to stick with systemd-based distros is that I’ve never had a problem with systemd. The “works for me” response can be irritating in response to problems with Linux, but I have no complaints in my own usage.

I prefer systemd over the old method. I was never entirely comfortable with SysVInit, with its need to manage shell scripts and runlevels. I cringed whenever I saw documentation on enabling and disabling services, even though it was something I rarely did on desktop systems, since most of them were set up with what they needed to run immediately.

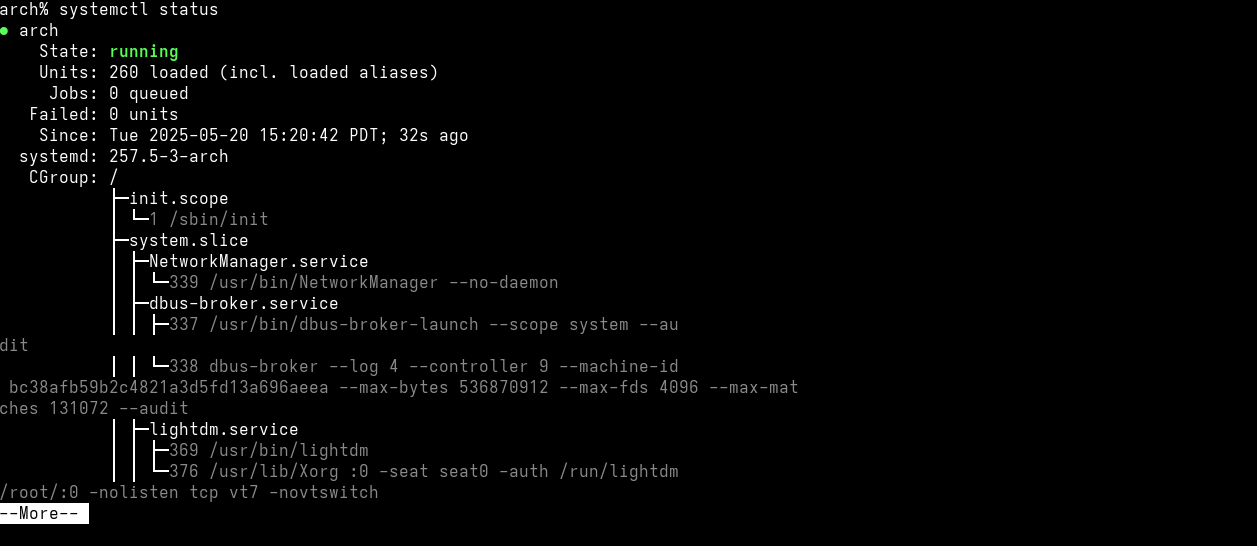

When I need to enable, disable, start, or stop services, I just run a quick systemctl command. That’s all it takes.

As a user who only starts and stops services some of the time, despite systemd’s supposed bloat, I find the systemctl command easy to understand.

I recently installed Arch in a virtual machine. I did have to enable some services, since Arch is more hands-on than other Linux distros. All it took was a few systemctl commands.

If systemd is Good Enough for Arch Linux…

One thing that finally tipped me in favor of systemd is that Arch Linux had switched to it. Arch already has a reputation for being geared toward sophisticated Linux users by putting them in more control over how their system is configured. You can choose which partitioning tool and boot loader, as well as the desktop environment, or even to install a desktop environment at all.

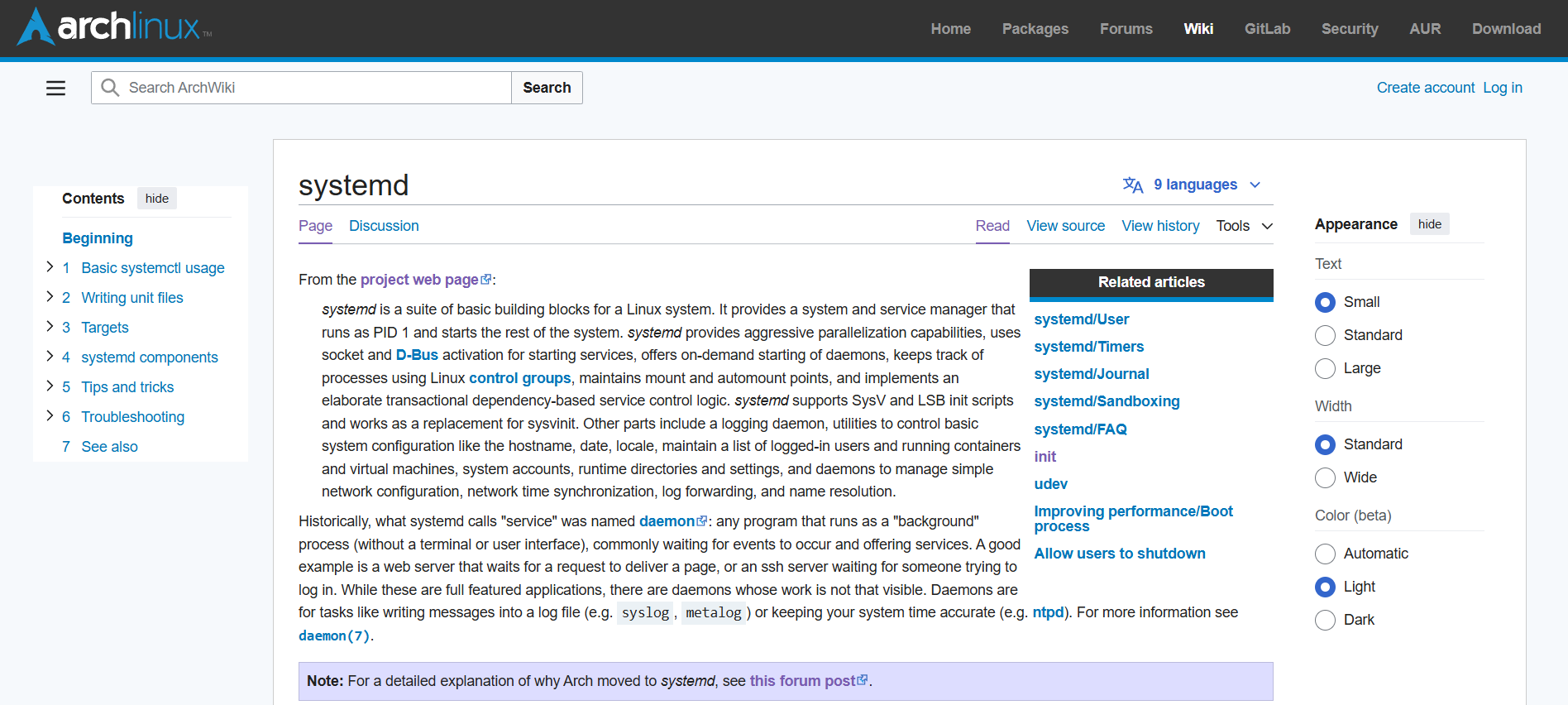

When I found an old forum post from one of the developers from 2012, linked from the Arch Wiki, I studied the case that the developer laid out. The developer cited the ability to know everything that was going on with the system, the ability to detect hotplugged devices, systemd’s modularity, security, and sandboxing features, as well as the systemd project’s cross-platform development.

According to the Arch Wiki, one of the distro’s guiding lights is “pragmatism”:

Arch is a pragmatic distribution rather than an ideological one. The principles here are only useful guidelines. Ultimately, design decisions are made on a case-by-case basis through developer consensus. Evidence-based technical analysis and debate are what matter, not politics or popular opinion.

Arch Linux has always struck me as a “Unixy” Linux distribution with its focus on text-based configuration and the amount of control it gives users. If Arch developers could see the merits of systemd despite its supposed “bloat,” I thought systemd was worth a serious look. Any lingering apprehension toward systemd vanished. This may seem like an argument from authority, but the Arch development team has earned my trust through their results.

Process Management Is a Small Part of My Linux Use

The init system may be an important part of Linux, but for me, it’s mostly behind the scenes. I rarely interact with it directly outside the systemctl command.

While it could be that launching programs throughout the day and closing them could be considered process management, most of the time, I think I can count the number of times I’ve interacted directly with systemd to manage processes via systemctl on one hand. On a desktop distro, it would probably be one or two times.

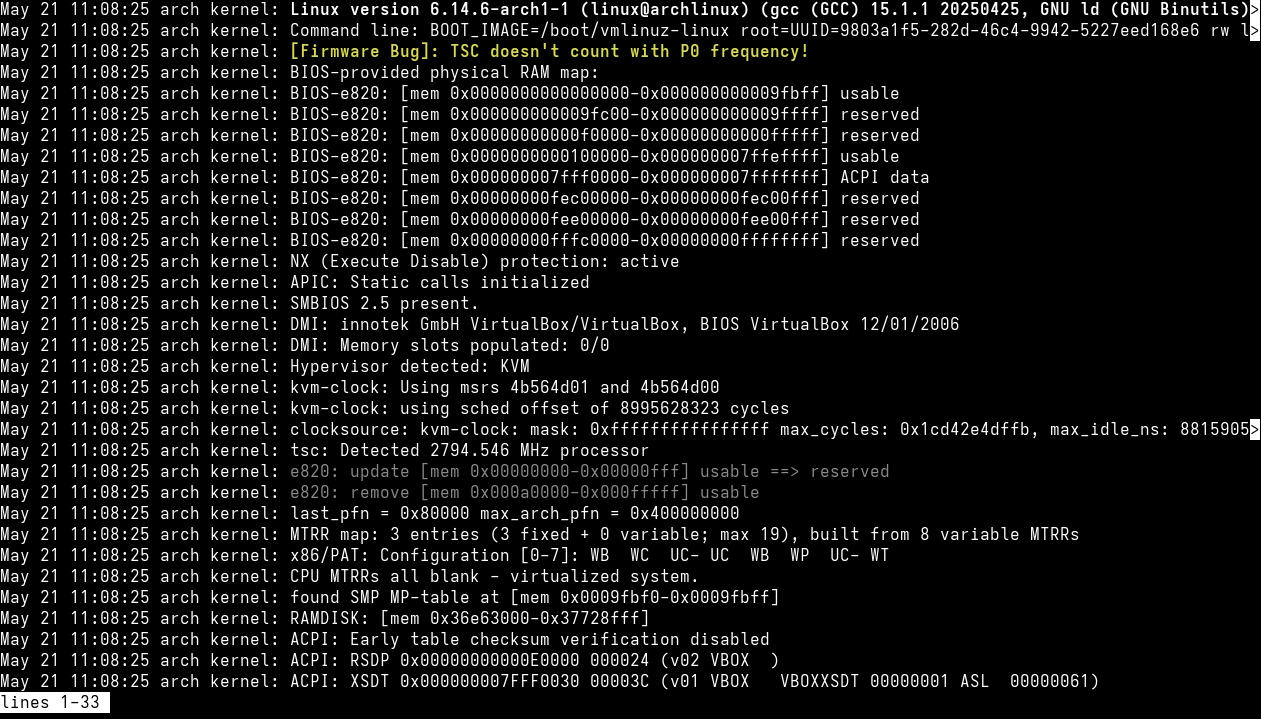

I do check the logs occasionally, like any user should. systemd’s binary logs have also been controversial, but the journalctl command is easy to use. Many of the logs on Ubuntu seem to be mirrored in the /var/log directory, so I can examine them with a regular text editor.

systemd-free Distros Don’t Impress Me That Much

The fact that systemd is in the background is one reason that distros that promote themselves as being systemd-free don’t impress me that much. I’ve explored a few recently, such as EXE GNU/Linux and Obarun. Distro makers are free to put in or not put in in their distros whatever they please.

When I evaluate distros for HTG, I try to take the position of an ordinary user, not some Linux hacker who has strong opinions for or against systemd. The user experience matters more than what’s under the hood.

A distro is going to have to rise or fall based on everything else it has. Some distros offer a unique experience, such as EXE GNU/Linux’s retro throwback designs.

Sometimes, Change Is Good

While the original System V init system worked well for many years, changes in the computer world finally made it obsolete in an increasingly mobile and online world.

There might be some concerns about the size of systemd or the supposed dominance of Linux development by Red Hat and its parent company, IBM.

The world changes, computer hardware changes, and operating system software changes with it. Operating systems have to serve users and run their programs. They have to evolve with what their users do with them. They can’t be museum pieces.