“To the average consumer, the pictures they take with their phone are often good enough,” Spectricity’s chief marketing officer, Henrik Andersen, told me during a Google Meet call during CES 2025. He was talking about the ongoing challenge of getting exciting new camera technology into our phones when the major players tend to be conservative in their approach, and unless you’re an enthusiast, the advancements may not appear all that meaningful at first.

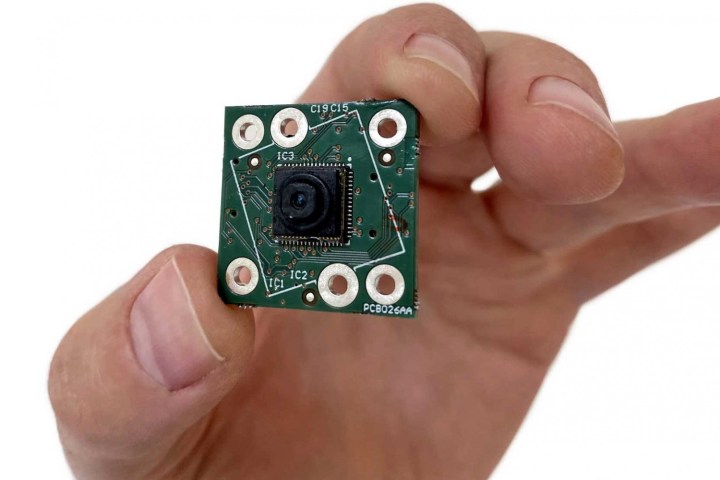

Spectricity produces something called a multispectral imager (MSI) sensor, which looks deep into visible light to bring more natural colors and vastly improved white balance to smartphone photos. I first encountered Spectricity’s tiny S1 sensor at CES 2023, and at the time, the firm had ambitions to introduce it into phones during 2024 and at higher volumes in 2025. This hasn’t played out quite as expected, and Andersen candidly explained the difficulties it faced with manufacturers, highlighting a problem all mobile tech fans have likely noticed. But Spectricity is adapting, and I had a fascinating glimpse at where its sensor is headed next.

Why aren’t phone makers using it?

A conservative approach from brands like Apple and Samsung when introducing new technology is expected and is often a point of contention for fans and buyers. But what about smaller brands looking for new ways to differentiate their devices and entice people to buy them? Wouldn’t a multispectral sensor be exactly the type of camera technology they’d adopt? A conservative strategy was just one of the hurdles Spectricity is working to overcome, as Anderson explained:

“Cost is always a major factor, and we’re adding basically another camera,” Anderson told me. “It’s also real estate in the phone, and there are some power requirements, too. [The sensor] doesn’t consume a lot of power, but [phone makers] squeeze everything they can out of the battery. So cost is clearly a barrier to overcome, and just getting that real estate space in the phone is tough, and we have to convince them it’s worth it.”

Then there’s the integration,” he continued. “A lot of smaller companies just work with the Qualcomm automatic white balance (AWB) system, and if Qualcomm doesn’t provide integration for an MSI, they have to do it themselves. We are working closely with Qualcomm to make this thing happen, but it’s a chicken and egg situation, because companies won’t put resources behind it unless there’s a demand from the customers.”

What else can the sensor do?

Anderson’s candid responses shine a light on why the mobile industry moves slowly and many complain about a lack of innovation. What’s also interesting is how Spectricity is approaching the situation. It has come to CES 2025 with the S1-A, a combined MSI and camera module that magnetically attaches to the back of a tablet and captures 15 channels of visible light, much more than the three channels captured by a normal RGB camera.

The S1-A isn’t for consumers but is a reference device Spectricity will supply to partners and developers. Until the S1-A’s arrival, it demonstrated the potential of its sensor using equipment most suited to lab use, so companies couldn’t easily go out into the field and test it. It’s also not targeting mobile with the SA-1. Instead, it’s using it to show different markets how a multispectral imaging sensor will benefit them.

One example is with Korean skincare brand Lululab. The sensor can be used for in-depth skin analysis, revealing blood volume, melatonin levels, pigmentation, and skin oxygenation. Using this data and complex AI models, Lululab can recommend everything from the correct treatment for dark circles under your eyes to acne relief and the right makeup products for your skin type. Spectricity’s software even provides a Pantone color code. Anderson talked about some of the other unusual applications for its sensor, which are being explored with the S1-A:

“One company is looking at wound care, where the spectral images show how a wound is healing, and another company is looking at how it can be used in food safety. Another wants to use the sensor in a robot vacuum for stain detection and to identify floor type.”

It shows the versatility of Spectricity’s sensor despite its most obvious use being alongside a camera in our smartphone. Currently, the S1-A sensor is compatible with a Samsung Galaxy S9 tablet, and it connects using a USB-C cable and syncs up with a custom app. Spectricity is working on adding other Android devices to the compatibility list and will introduce iOS support if there is demand.

Is this the end for multispectral sensors on phones?

The mobile industry hasn’t rushed to adopt true multispectral imagining sensors on phones. It’s unfortunate; in a demonstration, I saw just how effective they can be at balancing colors and white balance in challenging lighting, vastly improving the image taken by the camera’s RGB sensor on its own. It’s not a small alteration, and you don’t need to be an expert to see how it improves photos, making it all the more frustrating that we haven’t had the chance to try it out in the real world.

Has the industry’s slow pace ruined our chance of seeing how much difference a multispectral imaging sensor has on our photos? Maybe not. Anderson was open about the first multispectral imaging sensor arriving on a phone in late 2024 and it not being made by Spectricity. The sensor is part of the Huawei Mate 70 Pro’s camera, a device not yet released outside China.

“We’ve been testing out the photo quality, and we do see that the AWB has really improved,” Anderson commented, adding, “It seems a lot of the industry is looking at the market response to it.”

All it takes is for one device manufacturer to show the benefits of a multispectral imaging sensor and for owners to notice the difference when taking photos, and other phone makers are far more likely to follow. The Mate 70 Pro could be that device, but in the meantime, we may see a Spectricity sensor at work in other, less expected situations as we wait for the industry to slowly catch up.