5G mmWave is the fastest mobile network technology we have, hitting speeds of up to 10Gbps in the real world. Let’s explore what it actually is and learn how cellular networks work in the process. I know some of it sounds like Physics 101, but I promise this will help us get a deeper understanding.

What Exactly Is a Wave Anyway?

We’ve all seen waves on water when it’s disturbed. Suppose there is a buoy in that disturbed water (or anything that floats), you’d notice that it just bobs up and down without going anywhere. Why doesn’t it move back or forth like the waves seem to? Also, all that bobbing must require energy. Where did that energy come from?

The answer is it traveled outwards from the original source of the disturbance. Say someone dropped a pebble in still water, which made the wave. The expanding waves carried that pebble’s energy with them all the way to the buoy.

Why didn’t that energy push the buoy forward, though? That’s because even though it gives the illusion of rippling outwards, the water isn’t actually moving farther out. It just bounces up and down. So, to recap, the energy of the wave transfers far out, but the wave itself stays put. Just like how people create a wave in a stadium by sitting up and down.

Every wave obeys the same principles. For example, a wave would behave exactly the same way if you created a disturbance in air instead of water (that’s what sound is).

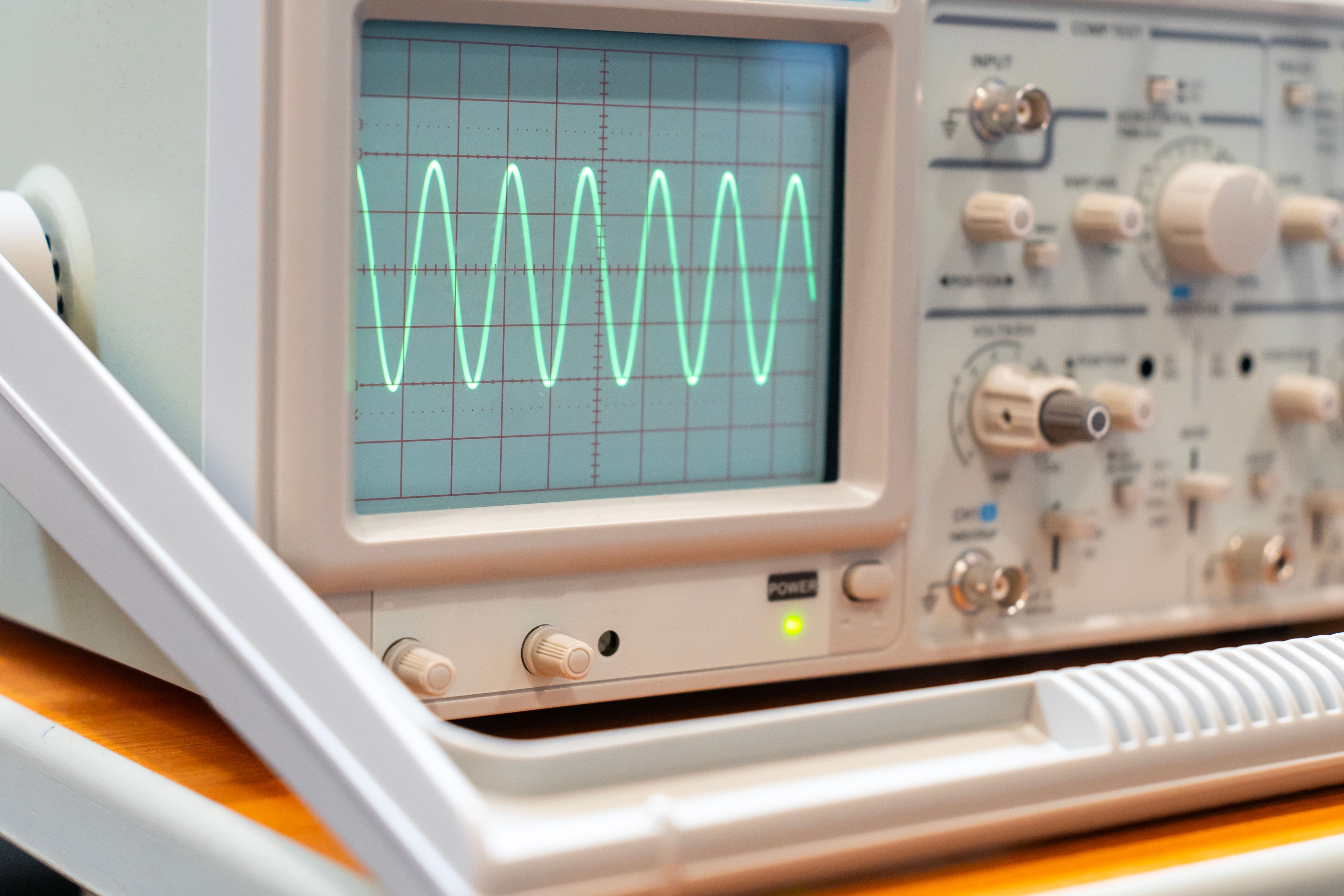

Scientifically speaking, there is a term for each of these behaviors and a way to quantify them. For example, if you count how many times the buoy bounces up and down in a second, that is its frequency. How far up and down the buoy travels every time is the amplitude of the wave. And if you take a ruler and measure the distance between the ripples, that would be its wavelength.

When the waves are packed closer together, the wavelength is shorter, and the frequency is higher. The frequency is lower, and the wavelength is longer when the waves are farther apart. As a rule, higher frequencies mean more energy and vice versa.

5G Is a Special Kind Of Wave

Waves are everywhere around us. The light we see can actually behave just like water waves. Unlike water or air waves though, it’s kind of a special wave that doesn’t need a material to spread out. It can just spread across empty space. This special type of wave is called an electromagnetic wave.

It’s made of an entire spectrum of different wavelengths, and a narrow band of that spectrum is what we perceive as visible light. All the colors we see are just different wavelengths on this spectrum. In simpler words, we only see a small slice of electromagnetic waves, and the rest is invisible.

When an electromagnetic wave has a very short wavelength, it can be a gamma ray, X-ray, or ultraviolet wave (the same UV rays that we’re supposed to avoid when out in the sun). On the opposite end, when it has the longest wavelength possible, it’s a radio wave.

Radio waves can travel incredible distances because they have the longest wavelengths and very low frequencies. That’s why we use them for wireless communication. Wi-Fi and cellular, including 5G, are actually radio waves.

Waves Can Carry A Lot of Data, Really Fast

How can a wave carry a message or internet data packets though? It sounds mind-boggling, but the key lies in the simplicity of the language of the message itself.

You’ve probably heard about Morse code. It’s a language made entirely of dots and dashes. Then there’s binary, the language of 1s and 0s, which computers read and understand.

Remember the buoy that bobs up and down when you drop a pebble in the water? You could create a language out of it to send a message. The height the buoy bobs up to could be the code: the higher height could be 1, and the lower height could be zero. You could drop a large rock to “encode” a 1 and a small pebble to “encode” a 0. It would be pretty clunky and slow, but in principle, someone far off could observe the buoy and interpret the message you sent across the waves.

That is basically how radio communication works. A transmitter device encodes 1s and 0s by changing the frequency, amplitude (just like our buoy), or phase of the wave. Technically, it’s called modulation.

A pattern of 1s and 0s can be mapped or “encoded” onto a wave because the transmitter can create extremely precise disturbances, which receiver hardware interprets and “decodes” into 1s and 0s. You can see how a wave with a higher frequency (more vibrations per second) and a shorter wavelength will allow you to encode more information since there are more slots or opportunities to modulate the bits of the wave.

We already know that cellular networks run on radio waves, and radio waves can have wavelengths as small as a single millimeter or as long as several miles. That’s key.

5G mmWave Explained

With that, we have all the puzzle pieces to illustrate what 5G mmWave is.

Early generations of cellular (1G and 2G) used radio waves that vibrate around 1-2 billion times per second (1-2GHz) and have wavelengths of about 1 foot. It sounds fast, but the first generation couldn’t even send text messages. The third generation (3G) upped the frequency to 2.5 GHz and cut the wavelength in half. With 3G, you can browse the internet and stream in SD. With the fourth generation (4G), the frequency went all the way up to 8 GHz, and the wavelength shortened to 1.5 inches, which allowed for HD streaming and fast browsing. It reaches about 50Mbps to 100Mbps in the real world.

5G is a leap forward because it operates at a whopping 100 GHz (that’s one hundred billion times per second). Its wavelength can be as short as a millimeter (mm); hence the name. So that’s what 5G mmWave is: a cellular network operating at a tremendously high frequency and wavelengths of 1mm, hitting an average download speed of 2.5Gbps.

What it Means For Us

5G isn’t just faster than 4G; it’s also way more responsive. The latency can be as low as 1 millisecond, which is near instant. That means no lag in online gaming and 4K or 8K streaming without any buffering. The near-instant response time is also perfect for Internet-of-Things devices, AR, self-driving cars, and tech that require low latency.

In addition to ultra-fast data transmission and incredibly low latency, 5G mmWave also supports more bandwidth compared to traditional networks (a lot more devices can connect to it without suffering network congestion).

Limitations of 5G mmWave

Every cellular technology before 5G, including 4G, used a single frequency band. 5G uses many. The 5G mmWave is only one of those many bands. There’s also 5G Sub-6 GHz, which operates around the same frequencies as 4G. Then there’s Sub-1 GHz, which uses even lower frequencies. 5G frequency bands can be high-frequency, mid-frequency, and low-frequency. What gives?

Since 5G waves are packed tightly together (compared to the old kind of radio waves), they cannot spread far. Buildings, trees, and even rain or snow can obstruct 5G mmWave.

That’s why this technology is not too widespread. It takes a dense network of small cells to cover even a few city blocks as opposed to 4G, which relies on large cell towers that typically cover several miles.

5G mmWave is our latest and farthest step into seamless wireless communication, but it may not see the widespread adoption we’ve seen with the previous generations. Nevertheless, seeing gigabit speeds on your phone’s data connection will always make you feel like the future is already here.